As we approach the 11th anniversary of our book, Conscious Capitalism: Liberating the Heroic Spirit of Business, co-authored by my dear friend and Babson business professor, Raj Sisodia, I’ve spent considerable time contemplating the evolving perception of conscious capitalism. Lately, I’ve grown increasingly concerned about how it’s often misrepresented and misunderstood, especially within the context of ongoing cultural debates in the U.S. and globally. In this blog post, I aim to provide my most recent thoughts on conscious capitalism, address its core principles, and respond to common misconceptions and critiques.

Defining Conscious Capitalism

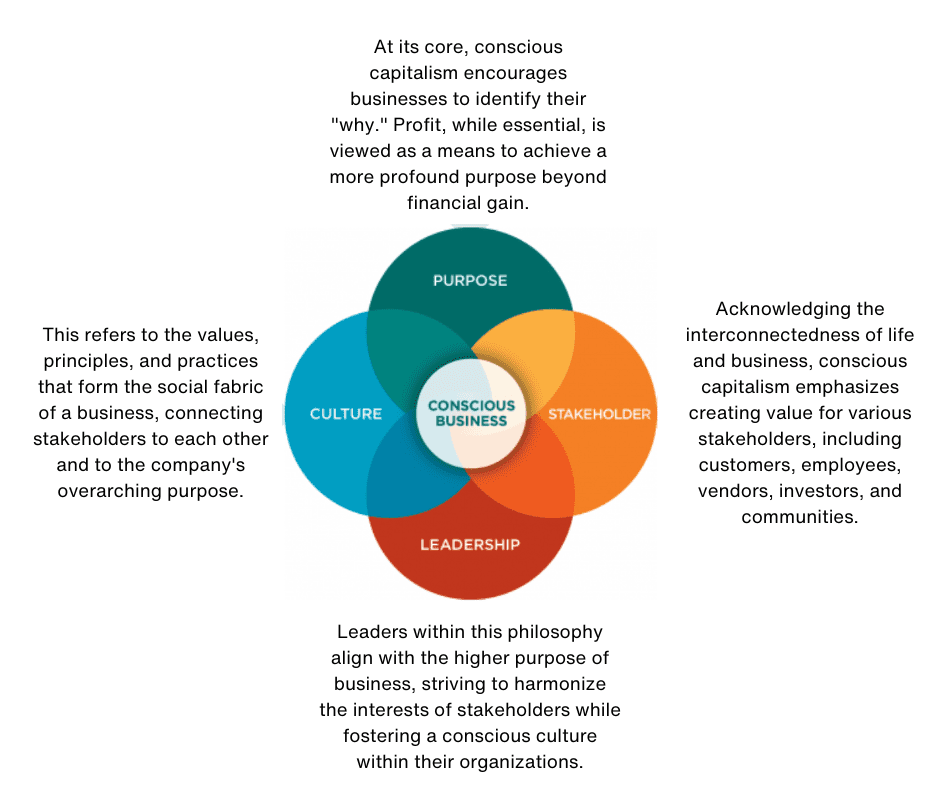

First and foremost, it’s crucial to clarify what conscious capitalism is and what it isn’t. Conscious capitalism is not an economic system, but rather a management philosophy—a unique approach to how businesses are led and managed. It rests on four fundamental pillars, which are explained on the website of our nonprofit, Conscious Capitalism, in detail and are summarized below:

A Framework for Understanding Worldviews

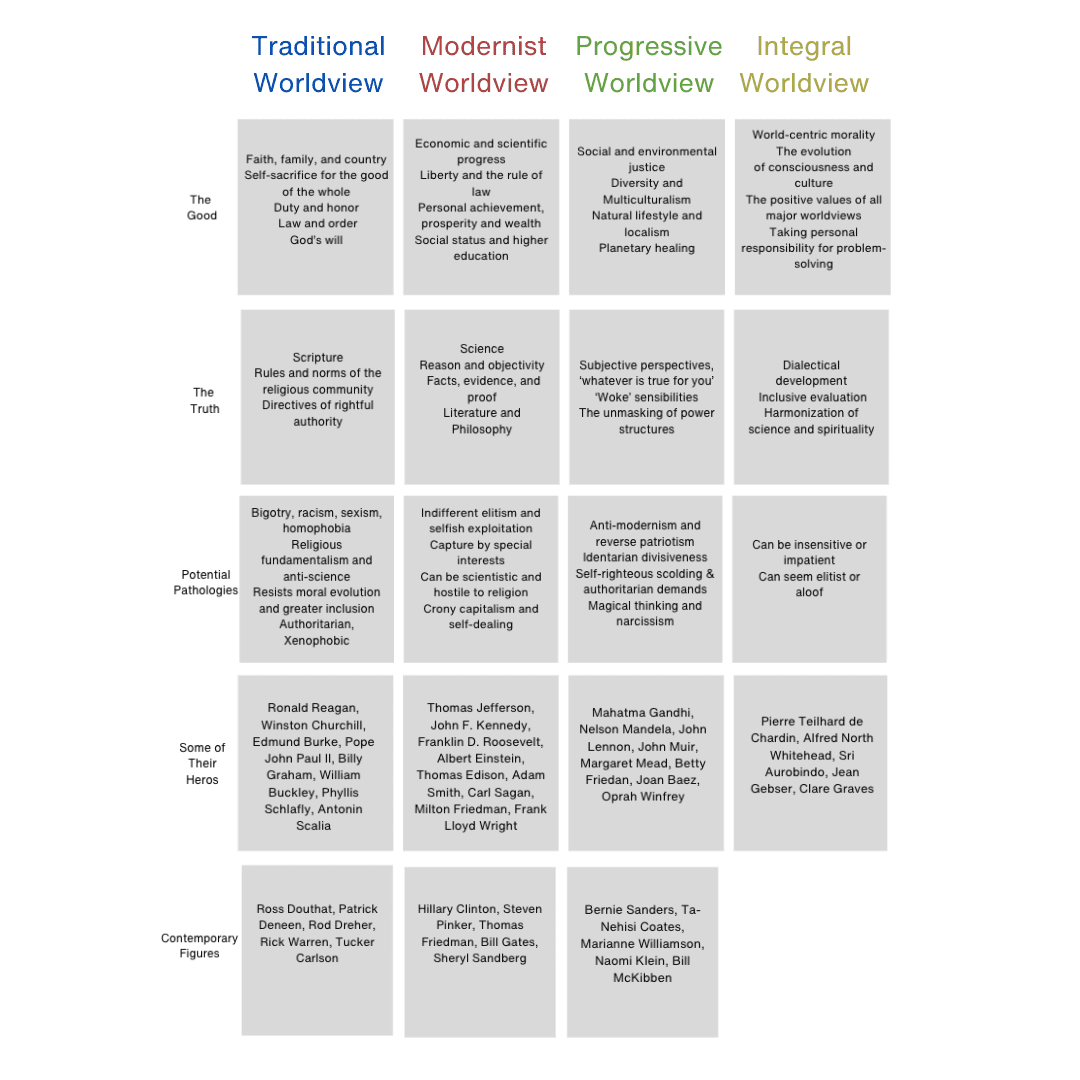

To better appreciate conscious capitalism, it’s valuable to explore the concept of worldviews, as outlined in Integral theory by thinkers like Ken Wilber (A Theory of Everything), Don Beck (Spiral Dynamics), Steve McIntosh (Integral Consciousness and Developmental Politics), and Carter Phipps (Evolutionaries). These worldviews offer different perspectives on life and culture. While there are at least eight worldview categories, we will focus on four primary ones for the sake of this discussion:

1. Traditionalism: Rooted in the belief that the universe was created by a higher power, traditionalists emphasize family, church, community, and country, and believe in authority, rules, law, and order. They value loyalty, faith, service, security, and conformity, and frequently have a sense of higher purpose or calling.

2. Modernism: Capitalism began and prospered under the modernist worldview. Modernists see the universe as an objective entity and rely on science, rationality, and logic. They appreciate individual autonomy, progress, capitalism, and meritocracy, and are optimistic about continued scientific and technological progress in the future.

3. Postmodernism: Postmodernists see the world as relativistic and pluralistic. They believe truth is subjective and qualitative, advocating for authenticity, diversity, equality, and social justice. Postmodernism is skeptical about all meta-narratives. They believe such narratives are not “objectively true,” but merely represent the beliefs of the people that are in power, which use them to oppress the less powerful.

4. Integralism: A cluster of worldviews, integralism perceives the universe, life, people, and culture as continually evolving. They integrate various methods, including science, spirituality, rationality, and intersubjectivity, emphasizing values like spiritual growth, wisdom, global peace, and universal compassion. This worldview believes in the importance of personal and spiritual growth and sees cultural evolution as the primary solution to many of our global challenges.

The Challenge of Conscious Capitalism’s Brand Name

To provide a backdrop for my thoughts on conscious capitalism, let’s briefly explore the developmental framework of the four major worldviews prevalent in highly developed countries, including the United States. Central to my discussion is the brand name itself – Conscious Capitalism.

“Capitalism” typically aligns with modernistic worldviews, while “conscious” has stronger associations with postmodern worldviews. This fusion gives the brand its potency and memorability, bridging both worldviews. However, it also generates confusion and tension.

From the modernistic viewpoint, there seems little reason to connect “conscious” with capitalism. This worldview generally perceives capitalism as inherently positive and is skeptical about why it should be modified by a term often linked (albeit unconsciously) with postmodernism, which often critiques capitalism.

For many with postmodern perspectives, the term “conscious capitalism” appears contradictory, as they believe capitalism is irreparable and should be replaced with something superior. In my first conscious capitalism meeting about 17 years ago, we had just 15 attendees. Only one person, myself, held a positive view of capitalism. The remaining 14 participants, all with postmodern worldviews, embraced the idea of “conscious” but not “capitalism.” Their vision aimed at reinventing capitalism by having corporations democratically owned and controlled by “society” rather than investors, essentially shifting from capitalism to anti-capitalism. Such a reinvention would effectively dismantle capitalism, which has been the major source of innovation and progress for the past three centuries.

The following year, we convened for another meeting, which proved more successful. Most participants were either modernists or integralists, more supportive of traditional capitalism. Postmodernists were a minority in attendance. The movement began growing steadily, but we faced an ongoing challenge: preventing postmodernists from steering the Conscious Capitalism movement toward a reflection of solely postmodern values, while dismissing the modernistic core elements intrinsic to traditional capitalism.

Many postmodernists attracted to the movement are not entrepreneurs – they’re unfamiliar with the arduous task of building successful and profitable businesses. They include consultants and academics who often lack firsthand experience in the fiercely competitive real-world marketplace, where survival and flourishing are formidable tasks. Without financial success, a business ultimately perishes, and its conscious aspects necessarily die too.

Diverse Worldviews on Business Purpose

Why does business exist? The purpose of a business varies depending on the observer’s worldview. From a modernist perspective, businesses fundamentally aim to create value for customers and generate profits through voluntary exchange with them. This view often further simplifies business purpose, famously expressed by Milton Friedman as the singular responsibility of business being to increase its profits.

In contrast, postmodernists critique this viewpoint, accusing it of selfishness and greed, claiming that it neglects stakeholders such as customers, employees, suppliers, communities, and the environment. Modernists often counter by suggesting that these other stakeholders should look out for themselves, further fueling the postmodern belief that capitalism’s pursuit of profit leads to negative consequences.

Integral thinking, however, recognizes the interdependencies among major stakeholders and acknowledges capitalism’s role in global economic progress. Conscious capitalism, as we’ve defined it in our book, represents an integral response to business purpose, synthesizing the best aspects of modernistic capitalism with insights from postmodern critiques. This creates a more adaptive form of capitalism suitable for the 21st century.

The Significance of Stakeholders in Conscious Capitalism

Within conscious capitalism, stakeholders play a pivotal role as the second pillar of our framework. Major stakeholders, including customers, team members, investors, suppliers, and local communities, form an interconnected business ecosystem. They engage with the business voluntarily, aiming for mutual benefit, emphasizing the importance of seeking win-win-win solutions that create value for all.

While all stakeholders matter, they are not of equal significance to the business. The top three stakeholders, customers, team members, and owners/investors, are interdependent. For a business to thrive long-term, it must create value for all three. From my perspective, their ranking in importance is as follows: customers, owners/investors, and team members. In some cases, such as small businesses, team members may be absent, with owners directly engaging with customers.

Suppliers, local communities, and larger communities are also important stakeholders, but their impact on business success is typically less than that of the primary stakeholders. Tertiary stakeholders such as the government, media, critics, activists, and the environment should be taken into account as they can all have impacts on the business, but because they are not voluntarily exchanging with the business for mutual gains, they are not as important to the business as the other stakeholders are.

The Debate Over Stakeholder Control

Recently, there has been a trend toward diminishing the role of owners and investors in the stakeholder hierarchy. This movement is primarily driven by anti-capitalists who advocate for redistributing control over businesses among stakeholders like customers, employees, and community representatives, often appointed by governments or social activists.

This shift in control away from financial owners poses significant risks. If owners lose control, capitalism, the primary driver of innovation and human progress, may decline as businesses become increasingly controlled by governmental bureaucrats who will deemphasize the economic purpose of the business. Economic freedom and innovation could stagnate, eventually leading to societal decline, a pattern observed throughout history when such liberties are curtailed.

Upholding Meritocracy’s Vital Role

In the United States, the concept of meritocracy faces criticism from radical postmodernists who argue that our entire economic and social system is inherently unjust due to its historical reliance on racial and gender discrimination and oppression. They view meritocracy as yet another narrative employed by those in power to legitimize and safeguard their positions, leading them to dismiss it as inconsequential.

It is not my intention to delve into a historical debate about the United States or any other country. Throughout history, racism, gender discrimination, and various forms of oppression have persisted across all cultures, races, religions, and tribes. These issues are neither new nor unique to the United States. What the postmodern perspective often overlooks is the ongoing evolution of culture and values and the failure to contextualize contemporary challenges within a proper historical framework. An impartial analysis would reveal that there is significantly less gender discrimination, racism, and oppression in the United States today compared to 50 years ago or any other period in our history. If that is not true, then when exactly was it better in the past 400 years than it is today? There has never been a better time to be alive or to be an American than today.

I firmly believe that the ideal of meritocracy holds immense importance and serves as the key to the eventual eradication of all forms of discrimination based on race, gender, sexual preference, and more. Meritocracy, as defined by the Merriam-Webster dictionary, represents a system where individuals ascend to positions of success, power, and influence solely based on their demonstrated abilities and merit.

In the realm of conscious business, it is imperative to never discriminate based on race, gender, sexual preferences, or religious or political beliefs. Conscious businesses aspire to transcend racial, gender, religious, and political distinctions. Every individual warrants respect, dignity, and love without exceptions.

Discrimination within conscious businesses should exclusively focus on competence. To fully honor our ethical obligations to stakeholders, businesses must be structured to recruit, train, and elevate the most qualified and competent individuals. Any deviation from this meritocratic approach diminishes our capacity to fulfill our purpose and meet our obligations to our stakeholder community.

Live on the Higher Ground and Evolve to an Integral Worldview

Conscious leaders must live on the Higher Ground. The Higher Ground sees the truth and beauty of different perspectives and is able to synthesize them into solutions that appeal to almost everyone.

The win-lose mindset is how most people think. This is how sports and most games work—only a few winners and many losers. It is how most people think about life, business, and capitalism, but it is not true for business or capitalism, and it need not be true for your own life. The conscious business operates within a win-win-win mindset. Good for me, good for you, good for all of us. It looks for ways for all of the stakeholders to win. It looks for synergies rather than tradeoffs.

When we look for win-win-win solutions, we usually can find them. Most tradeoffs are a failure of imagination and creativity. That being said, sometimes we are unable to find win-win-win solutions, and tradeoffs become unavoidable. Ultimately, utopia isn’t possible—at least not until cultures and human nature evolve much further. We must always try to do the very best that we are capable of doing, knowing that it is unlikely to be perfect – “the perfect is the enemy of the good.”

For me, conscious capitalism is meant to be understood as the management philosophy from the perspective of the integral worldview. It takes the best elements from traditionalism, modernism, and postmodernism and synthesizes them into ways of managing and leading that will help evolve our world forward in many positive ways.